Virée de Galerne

- View a machine-translated version of the French article.

- Machine translation, like DeepL or Google Translate, is a useful starting point for translations, but translators must revise errors as necessary and confirm that the translation is accurate, rather than simply copy-pasting machine-translated text into the English Wikipedia.

- Do not translate text that appears unreliable or low-quality. If possible, verify the text with references provided in the foreign-language article.

- You must provide copyright attribution in the edit summary accompanying your translation by providing an interlanguage link to the source of your translation. A model attribution edit summary is

Content in this edit is translated from the existing French Wikipedia article at [[:fr:Virée de Galerne]]; see its history for attribution. - You may also add the template

{{Translated|fr|Virée de Galerne}}to the talk page. - For more guidance, see Wikipedia:Translation.

| Virée de Galerne | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the war in the Vendée | |||||||

The wounded General Lescure crosses the Loire at Saint-Florent | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Republicans Republicans |  Vendéens Vendéens  Chouans Chouans | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Armée de l'Ouest ~50,000–100,000 (?) | 60,000 to 100,000 people of which: 20,000–30,000 Vendéens 6,000–10,000 Chouans 30,000–60,000 non-combatants (old people, wounded, women and children) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~ 10,000 dead (?) | 50,000–70,000 dead | ||||||

- v

- t

- e

- 1st Machecoul

- Jallais

- 1st Cholet

- Pont-Charrault

- 1st Pornic

- 1st Sables-d'Olonne

- 2nd Pornic

- 2nd Sables-d'Olonne

- 1st Coron

- Chemillé

- Aubiers

- Challans

- Saint-Gervais

- Vezins

- 1st Port-Saint-Pierre

- 2nd Machecoul

- 1st Beaupréau

- 1st Beaulieu-sous-la-Roche

- 1st Legé

- Thouars

- 1st Saint-Colombin

- 2nd Port-Saint-Père

- 1st La Châtaigneraie

- Palluau

- Fontenay-le-Comte

- 3rd Machecoul

- Doué

- Montreuil-Bellay

- Saumur

- 1st Luçon

- Nantes

- Parthenay

- 1st Moulin-aux-Chèvres

- 1st Châtillon

- Martigné-Briand

- Vihiers

- Ponts-de-Cé

- 2nd Luçon

- Château d'Aux

- 3rd Luçon

- La Roche-sur-Yon

- Vertou

- Chantonnay

- Vrines

- 1st Montaigu

- Tiffauges

- Coron

- Pont-Barré

- 2nd Montaigu

- Saint-Fulgent

- Pallet

- 1st Noirmoutier

- Treize-Septiers

- 2nd Moulin-aux-Chèvres

- 2nd Châtillon

- 2nd Noirmoutier

- La Tremblaye

- 2nd Cholet

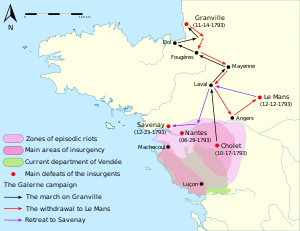

The Virée de Galerne was a military operation of the war in the Vendée during the French Revolutionary Wars across Brittany and Normandy. It takes its name from French virée (turn) and Breton gwalarn (northwest wind).

It concerns the Vendean army's crossing of the river Loire after their defeat in the Battle of Cholet on 17 October 1793 and its march to Granville in the hope of finding reinforcements there from England. Unable to take Granville on 14 November 1793, it fell back towards Savenay (23 December 1793) where it was completely destroyed by Republican troops under Kléber. The battle of Savenay marked the end of what would come to be called the First War in the Vendée.

Course

Rout at Cholet

On 17 October 1793, the Republican Army of the West coordinated an attack on the Vendéen Royalists and squeezed them into a pocket at Cholet. Encircled, the Catholic and Royal Army of Anjou and Haut-Poitou desperately attempted to resist but were decisively beaten. In the battle, Charles de Bonchamps was mortally wounded and 8,000 Vendéen Royalists were estimated to be killed, wounded or missing in action. With no choice, the Vendéen forces chose to take the only escape route open and fall back first to Beaupréau to the northwest then later to Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, where they were cornered in a bend of the river Loire.[1]

The Republicans' situation

The Army of the West finally managed to coordinate their attacks properly and defeat the Vendéen forces. After the battle of Cholet however, they made the mistake of believing the war had been definitively won, so they delayed their attack on Saint-Florent-le-Vieil. When they finally entered the town, it was deserted. Until October, the main weakness of the Republican troops was their lack of coordination, due to their division into several armies, and the rivalries of their leaders. The Committee of Public Safety put an end to this division when, on October 1st, it ordered the creation of a single army under a single command: the Army of the West. This army, created by the merger of the Army of the Coasts of La Rochelle, the Army of Mainz and the Nantes staff, previously under the command of the Army of the Coasts of Brest, was placed under the command of general sans-culotte Jean Léchelle. However, his incompetence soon became well known. As a result, several representatives-on-mission unofficially granted command to Jean-Baptiste Kléber. The main officers of this army were Michel Armand de Bacharetie de Beaupuy, Nicolas Haxo, François-Séverin Marceau-Desgraviers, François-Joseph Westermann and Alexis Chalbos. These generals were accompanied and supervised by several representatives-on-mission, including Antoine Merlin de Thionville, Pierre Bourbotte, Pierre-Louis Prieur and Jean-Baptiste Carrier. When the Army set out in pursuit of the Vendéens, it was 30,000 men strong.

North of the Loire, the Republican forces of the Army of the Coasts of Brest, commanded by general Jean Antoine Rossignol, were dispersed. This army, tasked with protecting the coast against an English attack or landing, controlled Brittany and Mainz, but its troops were mainly concentrated in coastal towns. Also, inland, Republican troops, underestimating the Vendéens, were systematically swept aside. Soon, they had to ask for reinforcements from the Army of the Coasts of Cherbourg, based in Normandy. The Vendéens managed to reach Laval without encountering any serious resistance, and these few easy victories even had the advantage of boosting their morale. The Republicans reacted by mobilising 1,500 national guards from Manche and 3,000 volunteers from Brittany, mainly from Trégor and Cornouaille who joined the Republican army with enthusiasm.[2]

Vendéen victories

After occupying Varades, the Vendéen general staff decided to march on Laval, in the former lands of the Prince of Talmont. The latter was convinced that his influence would provoke an insurrection in the country. On 20 October, the Vendeans reached Candé, then Château-Gontier on the 21st, meeting little resistance. On 22 October, they seized Laval after a short battle. The generals then decided to give their men a few days' rest. However, on the same day, the Republican forces of the Army of the West crossed the Loire at Angers and Nantes, determined to pursue the "Brigands". Only Nicolas Haxo remained in the Vendée with his division, in order to fight Charette's troops. On 25 October, the Republican vanguard, 4,000 men strong, commanded by Westermann and Beaupuy, entered Château-Gontier. The republicans were exhausted, but Westermann refused to wait for the bulk of the army and, the very next day, he launched an attack on Laval. It was a rout for the Republican forces who lost 1,600 men at Croix-Bataille.[3]

The next day, Westermann was joined at Villiers-Charlemagne by the rest of the army, commanded by Jean Léchelle. He immediately decided to launch a new attack. Despite the opposition of Kléber, who wanted to rest the troops, the Republicans attacked Laval again on 26 October. The stupidity of Léchelle's plan caused a new rout in the vicinity of Entrammes, and the Republicans had to flee to Lion-d'Angers. In the pursuit, the Vendeans even retook Château-Gontier where General Beaupuy was seriously wounded. The Republicans had 4,000 killed and wounded out of 20,000 men; the Vendeans had only 400 dead and 1,200 wounded out of 25,000 men.[4]

A few days later, Léchelle was arrested on the orders of Merlin de Thionville and sent to Nantes, where he committed suicide on 11 November. The day after the battle, as the Vendéens returned to Laval, Kléber decided to return to Angers with the army in order to reorganize his forces. The representatives appointed Alexis Chalbos as acting general-in-chief.[5]

The Chouans

The march on Granville

Battle of Dol

Retreat to the Loire

Rout at Le Mans

Destruction of the Catholic and Royal Army

Repression and reprisals

Timeline

- 18 October: The Vendéens cross the Loire at Saint-Florent-le-Vieil.

- 19 October: La Rochejaquelein elected generalissimo.

- 23 October: The Vendéens and Chouans take Laval, its 15,000 defenders beaten into retreat almost without a battle.

- 27 October: Battle of Entrames, Republicans crushed, Léchelle removed.

- 2 November: Capture of Mayenne.

- 3–4 November: Battle of Fougères.

- 4 November: Death of general Lescure.

- 9 November: The Vendéens are at Dol-de-Bretagne.

- 11 November: They are at Pontorson.

- 12 November: They reach Avranches.

- 14–15 November: Siege of Granville, Vendéens checked and about-turn.

- 16 November: Retreat to Avranches

- 18 November: Battle of Pontorson.

- 20–22 November: Battle of Dol.

- 23–24 November: The Vendéens take Fougères without a fight.

- 25 November: They retake Laval without a fight.

- 30 November: Battle of La Flèche.

- 3 December: Siege of Angers, Vendéens checked.

- 5 December: The Vendéens are at Baugé.

- 7 December: Retreat to La Flèche.

- 10–13 December: Battle of Le Mans

- 14 December: The Vendéens again return to Laval

- 16 December: They are at Ancenis; La Rochejaquelein, Jean-Nicolas Stofflet and 4,000 soldiers manage to cross the Loire.

- 17 December: Republican ships cut off the passage.

- 20 December: The Vendéens are at Blain.

- 23 December: Battle of Savenay, annihilation of the Vendéen army.

References

- ^ Smith, Digby (1998). The Greenhill Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill Books. p. 59.

- ^ Dupuy 2004, p. 129.

- ^ Gras 1994, p. 99.

- ^ Gras 1994, p. 100-101.

- ^ Hussenet 2007, p. 39.

Bibliography

- Brochet, Louis. "History of Vendée, Lower Poitou in France." Historie de Vendee.com, SEV, www.histoiredevendee.com/index.htm.

- Gabory, Emile. Les guerres de Vendée, Robert Laffont, 1989.

- Martin, Jean-Clément. Blancs et Bleus dans la Vendée déchirée, collection "Découvertes Gallimard" (nº 8), 1986.

- Secher, Reynald and René Le Honzec. Vendée, 1789–1801, cartoon, éditions Reynald Secher.

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book, Greenhill Books, 1989, ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Gras, Yves (1994). La Guerre de Vendée. Economica.

- Hussenet, Jacques (2007). Détruisez la Vendée ! Regards croisés sur les victimes et destructions de la guerre de Vendée. Centre vendéen de recherches historiques. ISBN 978-2911253348.

- Dupuy, Roger (2004). La Bretagne sous la Révolution et l’Empire, 1789-1815. Rennes.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

- History of the Vendée